KATE & TURNER

I walked into the Tate Britain because it was open…

I’m lying just a little here. I walked in because I’d been living in an 800 square foot cabin in the woods outside of Aspen, Colorado for thirteen years and I was starving for art. We moved to London in August 2020 so that I could attend the Royal College of Art for graduate studies in painting.

Knowing how contagious new art can be, I was, in a strange way, okay with the fact that the RCA’s studios were closed. While I was aching to see what was new and real in the world, at the same time I didn’t really want to go to gallery openings and see all the fabulous work that was out there.

Like a predilection for picking up accents, I didn’t want my work to get infected, pick up a twang or a lilt unintentionally. I am here to break my practice open like smashing your mother’s most precious possession on the floor, like smashing fluorescent bulbs in the dumpster because they explode in a way that makes me feel. I am here to hook in, undo, evolve and emerge. When I got here, I assumed the buzzing RCA studios and packs of us going from opening to opening would be the mechanism by which that happened.

Instead, it was the quiet of our newly sparsely furnished home and a tunnel of light into the faces of my tutors, calling in live from across the UK. The zoom scape became my umbilicus and, after an awkward three weeks where we all settled into the strange super-intimacy of having your tutor in your living room while you are in their spare bedroom with them, a rupture occurred.

I was going to the museums every time they reopened, I started at the National Gallery with Titian, he of the direct mark and the spank-bank bounty produced for King Phillip of Spain. I said hi to Rubens on the way by because his line, along with Schiele’s line, are like two limbs of poetry colliding in the center and burning me. Seeing the marks in person, especially the unfinished works, produces a Pavlovian salivary effect which could be off-putting if masks weren’t mandated. I don’t know if there’s a Schiele in London, I haven’t stumbled across it yet. But my Methodology of Holistic Research keeps unearthing Rubens.

I also, for comfort, seek my old friends in “contemporary” art which always brings my mother to me through the rent in space-time created by the work. She comes hurtling through the Albers and ends up sitting next to me looking at Klein, Judd, Rothko, Diebenkorn, Frankenthaler… the list is long, but then, so is my mother.

I’d been living in an “open studio” for a year and a half, all of my studio experience prior to that also included an alarming lack of silence, privacy, slowness, research, relationship, and autonomy. No matter how much I wished it was not, painting was always to some extent performative.

I had gone to Tate Britain to see the new home for the somber Bordeaux colored Rothkos, which was not nearly dark enough to capture the vibration of depression and introspection the way their old home had. While I was there, I bought my first museum membership. After all, we live here now. It didn’t matter that we’d have to book ahead or queue to go in. I was living where there was more art than I could eat in a lifetime. And I am voracious.

I returned because Turner’s Modern World was on and I was hungry. And then I met him. And everything changed. The Rupture happened. Like the rapture, only different.

It’s a strange relationship, really, I mean most Covid hook-ups are, and he is a bit of a recluse, quite quirky, and a bit depressed and withdrawn. And getting through to him could be challenging, I mean, he left drawings all over the place. I have always felt I needed to apologize for loving pre-contemporary art… as though it was the mark of one who refused to evolve. But Rubens, Gentileschi, Bonheur, Toulouse-Lautrec, and yes, okay Rembrandt, Titian, Fra Angelico, the list is embarrassingly endless and all of it is old. I’m in love with ghosts.

I had devoured them from my bed in the cabin in Colorado, recovering from cancer while doing my degree in Art History. The screen glowed blue inches from my face as I read, and looked, zooming as far in as the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art at the Met would let me. I would stare, late into the night between fits of neurasthenic symptoms left over from the effects of radiation sickness, at the rounded calf of Europa sliding off the bull, her soft, dimpled leg catching the smallest reflection of ochre fabric, at the dry brush, at the sfumato. Which stroke came first? What was from age and varnish? What was a choice, and what was happenstance? How could Titian just throw his brush full of white paint at a newly finished canvas like that? Wasn’t he scared?

Turner I had known by name, and as “the guy with the clouds” and “really great with light” but I’ve never been a landscape person, myself, as a painter that is. They always have wanted more than I could give and what, really, can beat the landscape itself? No, it was the flesh that captivated me, and still does.

But Turner pulled me into the vortex. And held me there, breathless, lashed to the mast against him as the storm raged all around us. I sat down in front of Snow Storm - Steam-Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth - originally exhibited in 1842 - and I didn’t leave for nearly four hours.

‘The ribs of Hephestus, greased with easy grace, are unrequited.’

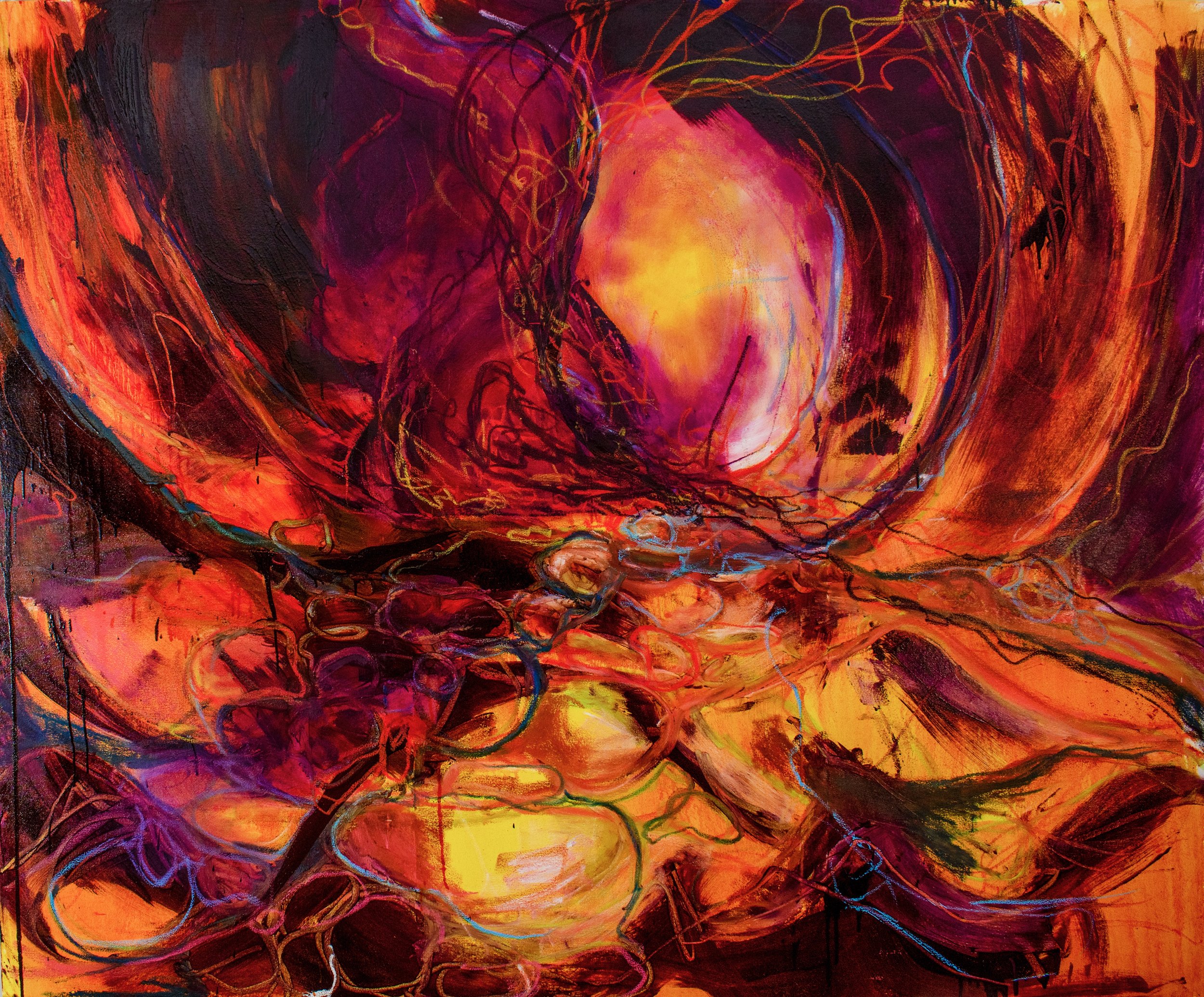

Kate Howe, 2021, oil paint and oil pastel on canvas, 160 x 200 cm. Collection: Turner, Painting.

‘I broke into your garden today and wrote you a letter from the bench under your window.’

Kate Howe, 2021, oil paint and oil pastel on canvas, 200 x 200 cm. Collection: Turner, Painting.

I took this photo on November 8 because my ass had fallen asleep and the guard really was starting to look at me funny. I needed to move on or they’d start to think I was either planning theft or rough sleeping, I’m not sure which.

I have a friend, we’ll call him S. (and he figures prominently in this story because it turns out he is the medium by which Turner first began to send me messages after our four-hour folding stool date. The DMs must have been broken.) S. says that the white in the center of the vortex is a series of signal flares, not a sail. He is probably right, but at this point, it doesn’t matter. We had a lively argument for about an hour shoving the proof of our position pulled up triumphantly on our phones into each other’s faces while our partners looked on, amused but sort of over it. But I’m getting ahead of myself. S., the rupture, and the time tunnel come later.

As I walked through Turner’s Modern World, I was looking for food. I often go to the museums to visit with a particular piece, my practice is to visit, sit in front of, and look and look and look, up close, from the side, from in front, in quiet, with a sketchbook (which often gets filled with words, more than marks).

Later, as I walk to the cafe for tea afterward, light headed and buzzing, I let myself get hailed by passing pieces that I’m unfamiliar with. I’ll walk over and have an awkward conversation, shifting weight, wondering who they are and what they are really like, and why they are here… if it stays with me after I go, I’ll visit again on purpose. In this way, my paintings have ever-expanding networks. I don’t always get on with all of the other paintings they introduce me to, but I inevitably learn the most from those by whom I am the most surprised to engage with.

I walked by Snow Storm and it did that thing. It wasn’t even an awkward conversation. It was that horrible thing where you fall, vertiginously and dangerously in love with something you don’t quite understand.

I had flipped open one of those fold-up stools that I always feel slightly bold and very silly and a bit selfish to carry, but am at the same time so grateful for. I looked and looked, sucked into the vortex of the image. I watched my eyes travel into and around the painting, spit back out only to be sucked back in. I started drawing the movement of my eyes.

In 2017, before I was diagnosed with cancer, I had gone to Superbike school and had learned to race a BMW s1000rr on the Las Vegas Motor Speedway. While I was at race school, I had the opportunity to look at a device that tracked pupil movement, and we could watch a Point of View video of the track unfolding before us, and two orange dots on the screen showed us where the pupils of the rider were focused.

I learned about saccade, the way the eye moves, the way it drops information as the eye skips along its resting points, the way the brain fills the gaps in. I love the study of how and why we work, how we interact with our own body machines, how we can learn to understand them better and exploit their capacities along the path of life. There’s more on that, but I’ll return to it. Remind me, I tend to wander. Filling in the gaps we edit out is something that Turner brought up to me later, through a conversation regarding horizon, a sextant, one-point perspective, and the human need for binary categorization. I know, intense right? So remind me of those things because I want to tell you, it was a great day that pushed me further into the wormhole.

Here I am, then, on this fabric folding stool in the middle of Tate Britain, watching my eyes race around the painting, trying to slow them down. I try entering from unpredictable points, I begin to mark down where they insist on traveling, I find new paths, but I also find that there is a surrender point like a swirling drain.

As usual, I fell in love with him before I knew he was depressed, withdrawn, difficult, odd. I don’t think it’s really love, this aggressive condition I find myself in periodically. It’s more like an addiction that my hedonistic self can’t resist tasting. I left Turner bruised, and when I looked down, this was all that was left.

‘If my eyes left grooves in the cleft of your rupture they would look like this.’

Kate Howe, 2021, oil paint and oil pastel on canvas, 160 x 200 cm.

Collection: Turner, Painting.

I went home and took out a sketchbook of delicious paper I’d picked up at the Wallace Collection during a Baroque feeding frenzy. (By the way, Rubens was in there. Twelve beautiful little tiny paintings hiding above a side table. I didn’t know Turner was stalking me. I was eating the cotton candy of swirling falling storming horses on a bridge, completely unprepared for what was coming.)

I started producing these drawings on my couch in oil pastel while trying to get a lease executed on a studio that I arranged in August from the States before we moved during the dip in the pandemic. It was November and still the lease wasn’t signed. The RCA studios were closed. I’ve been here six months and I’ve never stepped foot on campus.

My drawing language has changed, I noticed. Rather than a kind of mark for this and a kind of mark for that, now there are just marks. A language is coming. I’ve been making drawings of the pain in my body from the neurasthenic trauma left over from that radiation ‘mishap’ for about three years, now. Those marks have crept into everything.

My son, Bodhi, was really hoping that a ‘radiation mishap’ (not something you really ever want to tell your kid) would end up differently… for sure when they rotated that massive gimbal and aimed it at my breast, if it DID malfunction and shoot a structure-altering amount of radiation into my neck and chest, the result must certainly be some sort of superpower.

I’m going to hold on to that one and see what develops. Maybe I’m a radioactive late bloomer.

These drawings with Turner started to feel like the pain maps, like neuralgic firings, like my body, like my internal landscape, like caverns of fasciae, decades of emotion held in the body, stored in the tissue, forming into tumors, scooped out with a melon baller, pulled out like a string of pod filled kelp.

‘When I looked through my lens, there was your eye on the other end, looking through yours.’

Kate Howe, 2021, oil paint and oil pastel on canvas, 200 x 200 cm, currently on exhibition at True-house, London. Collection: Turner, Painting.

I ended up here, staring into the cavern of my heart, my life, all the threads that led me here. I was shedding old ideas, old impositions about myself. I have always been perceived as too odd, too big, too fast, too eager, too audacious, too ambitious, too willing, too intimidating, too kind, too boundaryless, too much about me. But what am I to do with this life other than investigating what is this living thing that I think is me?

I lost the studio. I filled the living room with drop cloths and turps. I knew I couldn’t play with Turner until I could meet him in private. He called to me. I sort of stalked him, I suppose, though his FaceBook leaves a lot to be desired, he is so opaque and secretive. Here is where S. comes in.

When we first came to London, we had angels at our sides. The story of the move is an epic in its own right. At the end of that epic, we were sweating in our hollow, echoey home, my mother holding us together like Peter Parker spinning webs that caught us as we fell and zipped us back into our family, into sanity. But there were bank accounts and quarantines and grocery deliveries and only one good chair. Enter P., the spouse of S. (how I met her is another great story, remind me and I’ll tell you later. But remind me, because I’ll forget.)

P. arrived at our doorstep during our quarantine with a bag of kale from their garden, wine, fresh basil, and a beautiful home grown squash. Every Saturday we started meeting P., S. and their family for stomps through Richmond, Kew, and Bushy Park. We went for an Urban Walk along the Thames to Petersham, our children chasing their children laughing and stomping in puddles, climbing trees, a decade-plus in the gap between them, none of them caring. We were outside, with good friends, and it was glorious. It was sanity. It was more physical activity than I’d done in a very very long time.

Early on, I’d told S. that I’d found Steam Boat at Tate Britain, and this crystalized some sort of tenacity of bringing up Turner at every, well, turn. I mean, honestly. Everywhere we went it was Turner this and Turner that. At first, I was being polite. The light, yes, the clouds, yes, the formal composition of Steam Boat, but I wasn’t going to suddenly depart on a rabid Turner journey. I had enjoyed our intense connection, and I was planning to use that moment as a map for the way I interacted with the work I went to visit in the future, in the hopes I might unlock some great secret of compositional awesomeness from the masters.

Now, this is the important part of the story. S.’s stories told while we were walking along with our kids, now that the museums were closed again, kept hooking me deeper. “And if you look here, at this island, Turner painted this from up there.” He would point and there was the protected view off of the terrace at Richmond. Later, we’d end up there, looking down.

Everywhere we went, there he was. We were wandering through Twickenham on the way to “a cool sculpture of naked ladies and sea horses” when we walked by Turner’s house.

Wait, what? This was just… on the way? Am I missing something? Am I not paying attention? Is Turner trying to get my attention? Yes, his actual house, with the blue plaque. I peeked over the fence at the garden. The house, like everything else in London, was closed.